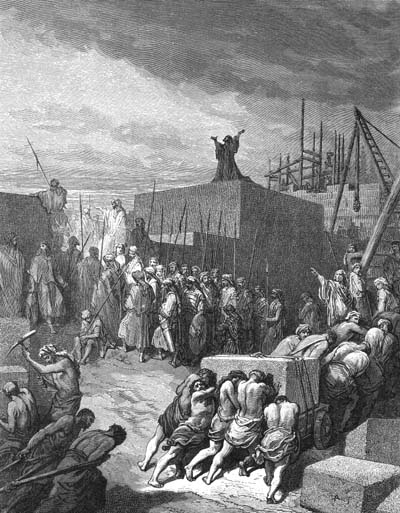

According to the fourth chapter of the Book of Ezra Zerubbabel, the leader of the Jews, has refused the Samaritan’s help in rebuilding the Temple in Jerusalem Jerusalem Jerusalem Persia

Biblical studies, biblical archaeology, biblical criticism, biblical authorship, biblical history.

Showing posts with label ezra-nehemiah. Show all posts

Showing posts with label ezra-nehemiah. Show all posts

Wednesday, August 8, 2012

Thursday, May 31, 2012

Laying the Foundations of Jerusalem Temple by Zerubbabel

Third chapter of Ezra book tells us how after the return from Babylon

First, they brought wood from Lebanon temple of Solomon

Premature celebration

In the plot line of this story about laying the foundations of the temple there is a confusing thing. For what did the Jews celebrate so joyfully with trumpets and cymbals? For what did they so grateful to God? What did the elders compare with the previous Solomon Temple? According to the storyline of Ezra book, they merely laid the foundation but rejoiced as if the temple has already been built.

Friday, May 4, 2012

The Story of Zerubbabel (Origin of the Guards Story)

One of the main characters of the biblical Book of Ezra is Zerubbabel. He heads the list of exiles that returned from the Babylonian captivity. After returning core group of exiles in the reign of the Persian king Cyrus Zerubbabel led the process of rebuilding the Temple in Jerusalem

However, the book didn't disclose the figure of Zerubbabel absolutely. Who was he? How did he become the leader of Jews? For what achievements? What is its fate?

Zerubbabel in the Book of Haggai

The book of Haggai gives us some information about this hero. But this information is largely contrary to the events of the book of Ezra. The book of Haggai tells us that Zerubbabel was governor of Judea at the time of king Darius. In those days people lived in Judea , but their life was uncomfortable. The land gave poor yields. Then God Yahweh through the prophet Haggai addressed the Jews and explained them that the reason of calamity is that the people of Judah didn’t rebuild the temple of God in Jerusalem. If they would rebuild it God will bless the land and it will give generous yields. Then residents of Judea led by the governor Zerubbabel began to build the temple and a few weeks they resumed it in the second year of the reign of king Darius.

Saturday, April 21, 2012

List of Exiles Who Returned from Babylonian Captivity

Textual problems

This list is also located in the Book of Nehemiah and in 1 Esdras. Moreover, 1 Esdras states that these exiles returned not at the time of King Cyrus, but at the time of King Darius. These three versions contain significant differences. They are different genealogies, numbers in groups, the number of donated money, the number of animals, the replacing of some groups. These discrepancies are chaotic in nature. Only part of them can be explained by errors of copyists. Therefore impossible to determine what list is original and what is derived from the original list.

The list indicated the total number of captives, which are 42,360 people. But in none of the lists in both books of Ezra and Nehemiah the total number of people does not exceed 34,000 people. Thus the lists are incomplete in all three books, the total number of listed exiles is 30000 - 34000 people.

Monday, January 16, 2012

The Story of Sheshbazzar

The book of Ezra tells us how after 70 years of Babylonian captivity the Jewish people returned to Judah and rebuilt Jerusalem Jerusalem

In the first chapter of the book (so called Story of Sheshbazzar) the Persian king Cyrus the Great issued an order and allowed the Jews return to Judah and rebuild the temple of Yahweh in Jerusalem. Then Cyrus sent to Jewish ruler Sheshbazzar the temple vessels which Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon brought from the temple of Solomon Babylon

Tuesday, November 1, 2011

Lester L. Grabbe, Ezra-Nehemiah (pdf)

The books of Ezra and Nehemiah have not been the most popular of the books in the Hebrew Bible. Yet they have had great influence on how the Jewish religion is assumed to have developed. They describe the reconstruction of the Jewish temple and state after their destruction by the Babylonians in 587/586 BCE and set the theme for the concerns and even the basis of Early Judaism which is usually seen as the Torah. The figure of Ezra has been profoundly associated with the origin or promulgation or interpretation of that Torah. The consequence is that the books of Ezra and Nehemiah are in many ways the foundation of much scholarship, not only about the development of the Jewish religion but even of how the Old Testament (OT) literature emerged.

The aim of this book is to make a contribution to a better understanding of these two books which, in my opinion, are crucial writings in the Hebrew Bible. My study has implications for the history of Israel and Judah Judah

Tuesday, October 4, 2011

The Two Recensions of the Book of Ezra: Ezra-Nehemiah (MT) and 1 Esdras (LXX)

Dieter Bohler

Abstract: Like Proverbs, Jeremiah and Daniel, the book of Ezra has been transmitted in two recensions: Ezra-Nehemiah in the Hebrew Bible and 1 Esdras in the Greek Bible. Each version has its own distinct literary shape. Both editions overlap in the account of Zerubbabel's temple building and Ezra's mission. In addition to this common material both versions contain special property: 1 Esdras starts with the last two chapters of Chronicles (Ezra MT

Sunday, August 7, 2011

Archaeology and the List of Returnees in the Books of Ezra and Nehemiah

Israel Finkelstein

The list of returnees (Ezra 2, 1-67; Nehemiah 7, 6-68) forms one of the cornerstones for the study of the province of Yehud

In a recent article (Finkelstein, in press) I questioned Nehemiah 3's description of the construction of the Jerusalem wall in the light of the archaeology of Jerusalem 2.5 hectares and was inhabited by 400-500 people. The archaeology of Jerusalem Jerusalem

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

Jerusalem in the Persian (and Early Hellenistic) Period and the Wall of Nehemiah

Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Vol 32.4 (2008): 501-520

Abstract

Knowledge of the archaeology of Jerusalem in the Persian (and Early Hellenistic) period — the size of the settlement and whether it was fortified — is crucial to understanding the history of the province of Yehud, the reality behind the book of Nehemiah and the process of compilation and redaction of certain biblical texts. It is therefore essential to look at the finds free of preconceptions (which may stem from the account in the book of Nehemiah) and only then attempt to merge archaeology and text.

The Current View

A considerable number of studies dealing with Jerusalem David

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)