According to the fourth chapter of the Book of Ezra Zerubbabel, the leader of the Jews, has refused the Samaritan’s help in rebuilding the Temple in Jerusalem Jerusalem Jerusalem Persia

Biblical studies, biblical archaeology, biblical criticism, biblical authorship, biblical history.

Showing posts with label textual criticism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label textual criticism. Show all posts

Wednesday, August 8, 2012

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

The Samaritan Version of Deuteronomy and the Origin of Deuteronomy

Prof. Dr. Stefan Schorch

Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg

Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg

Since 1953, when Albrecht Alt’s famous essay “Die Heimat des Deuteronomiums” was published, the question about the historical origin of Deuteronomy became an important issue in the research on the Hebrew Bible. Pointing especially to conceptual parallels between Deuteronomy and the Book of Hosea, Alt argued that Deuteronomy was not composed in Judah or in Jerusalem Israel

The idea of cult centralization appears for the first time in Deut 12:5:

You shall seek the place that the LORD your God will choose out of all your tribes (םכיטבש לכמ םכיהלא הוהי רחבי רשא םוקמה) as his habitation to put his name there. You shall go there…

This or similar formulae appear in the Book of Deuteronomy no less than 22 times. From the perspective of the received Masoretic text as a whole, the chosen place is clearly identified within the so-called Deuteronomistic history. Accordingly, the chosen place is Jerusalem

Monday, July 23, 2012

The Composition of the Pentateuch in Recent Research: A Teaching and Study Resource

John E. Anderson

I. Introduction

a. A lack of consensus in the last 30 years of scholarship

b. Both diachronic and synchronic approaches, documentarian and supplementarian approaches

c. To understand where we are, it is important—briefly—to look at from where we have come

II. Precursors to the Documentary Hypothesis: Working Towards JEDP (emergent source-criticism)

a. Spinoza (1670): “it is thus clearer than the sun at noonday that the Pentateuch was not written by Moses, but by someone who lived longer after Moses” (also Hobbes)

b. Jean Astruc (1753): isolates in Genesis an E and J source, with other independent material (yet did not challenge Mosaic authorship; Moses as redactor)

c. Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette (1780-1849) – decisive new phase in Pentateuchal investigations.

i. Saw religious institutions in Chronicles as retrojection from time of writing in late Persian / early Hellenistic period

1. thus reasonable that Pentateuchal legal material dates from time after monarchy

2. Pentateuchal narrative traditions cannot be used as historical source material

ii. 1805 – identified law book discovered by Josiah as early version of Deuteronomy (dates to 7th century)

d. H. Hupfeld (1853): in Genesis, identifies earlier E strand (corresponding to P) and later one; also an even later J document

e. K.H. Graf (1860s): Hupfeld’s E1 = Priestly and is latest, not earliest source (also Reuss prior and Kuenen after re-dating)

f. Julius Wellhausen (Prolegomena to the History of Israel

i. J & E = earliest sources; not always clearly distinguishable by use of divine names

1. combined by a Jahwistic editor

ii. Q (quattuor, four covenants) provides basic chronological structure for P material fitted in

iii. P

1. ritual law in Holiness Code (Leviticus 17-26), which is dependent on Ezekiel

2. thus P is the latest stage in editorial history of 5x/6x, save for some late Deuteronomic retouchings

iv. Deuteronomy

1. comes into existence independent of other sources

2. 622 with Josiah = first edition

3. familiar with JE but not P, so combined with JE prior to P ® JEDP

4. end result = publication of Pentateuch in final form at the time of Ezra (5th century)

v. Reveals an evolutionary view of Israelite religion (sees Moses as at end rather than beginning of historical process)

1. JE = nature religion, spontaneous worship arising in daily life and festivals tethered to agrarian calendar

2. D = centralization of worship, ends spontaneity, seals prophecy with emphasis on written law

3. P = denatured religion dominated by clerical caste that remade past in own image

vi. This view of sources dominated largely for nearly a century

Thursday, May 31, 2012

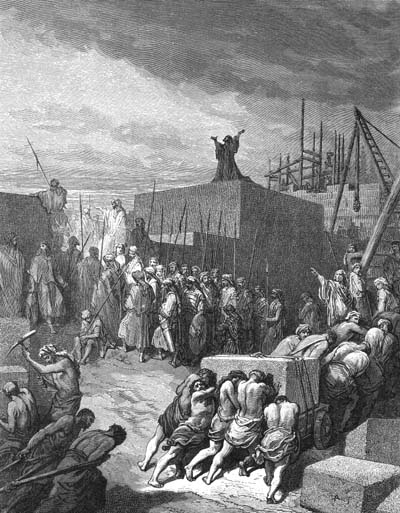

Laying the Foundations of Jerusalem Temple by Zerubbabel

Third chapter of Ezra book tells us how after the return from Babylon

First, they brought wood from Lebanon temple of Solomon

Premature celebration

In the plot line of this story about laying the foundations of the temple there is a confusing thing. For what did the Jews celebrate so joyfully with trumpets and cymbals? For what did they so grateful to God? What did the elders compare with the previous Solomon Temple? According to the storyline of Ezra book, they merely laid the foundation but rejoiced as if the temple has already been built.

Friday, May 4, 2012

The Story of Zerubbabel (Origin of the Guards Story)

One of the main characters of the biblical Book of Ezra is Zerubbabel. He heads the list of exiles that returned from the Babylonian captivity. After returning core group of exiles in the reign of the Persian king Cyrus Zerubbabel led the process of rebuilding the Temple in Jerusalem

However, the book didn't disclose the figure of Zerubbabel absolutely. Who was he? How did he become the leader of Jews? For what achievements? What is its fate?

Zerubbabel in the Book of Haggai

The book of Haggai gives us some information about this hero. But this information is largely contrary to the events of the book of Ezra. The book of Haggai tells us that Zerubbabel was governor of Judea at the time of king Darius. In those days people lived in Judea , but their life was uncomfortable. The land gave poor yields. Then God Yahweh through the prophet Haggai addressed the Jews and explained them that the reason of calamity is that the people of Judah didn’t rebuild the temple of God in Jerusalem. If they would rebuild it God will bless the land and it will give generous yields. Then residents of Judea led by the governor Zerubbabel began to build the temple and a few weeks they resumed it in the second year of the reign of king Darius.

Saturday, April 21, 2012

List of Exiles Who Returned from Babylonian Captivity

Textual problems

This list is also located in the Book of Nehemiah and in 1 Esdras. Moreover, 1 Esdras states that these exiles returned not at the time of King Cyrus, but at the time of King Darius. These three versions contain significant differences. They are different genealogies, numbers in groups, the number of donated money, the number of animals, the replacing of some groups. These discrepancies are chaotic in nature. Only part of them can be explained by errors of copyists. Therefore impossible to determine what list is original and what is derived from the original list.

The list indicated the total number of captives, which are 42,360 people. But in none of the lists in both books of Ezra and Nehemiah the total number of people does not exceed 34,000 people. Thus the lists are incomplete in all three books, the total number of listed exiles is 30000 - 34000 people.

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

Le Seigneur choisira-t-il le lieu de son nom ou l’a-t-il choisi? L’apport de la Bible Grecque ancienne á l’histoire du texte Samaritain et Massorétique

Adrian Schenker

1. La formule du Deutéronome : Le lieu que le Seigneur a choisi pour y établir son nom

L’étude d’un point particulier d’histoire du texte de la Bible hébraïque à la lumière de la Bible grecque ancienne est dédiée en hommage cordial à la collègue éminente Madame Raija Sollamo dont les echerches ont contribué si magnifiquement à la connaissance de la Bible grecque des Septante. Il s’agira d’une formule deutéronomique bien connue, différente dans la Bible massorétique et samaritaine. Qu’en est-il de son attestation dans la Bible grecque ancienne ? La formule elle-même se rencontre en trois formulations légèrement différentes 21 fois dans le Deutéronome. Voici la première forme : « le lieu que le Seigneur choisira (texte massorétique, tm) ou a choisi (Pentateuque samaritain [Sam]) pour y faire habiter son nom». Elle se trouve six fois en Dt 12 : 11 ; 14 : 23 ; 16 : 2,6,11 ; 26 : 2. La deuxième forme est la suivante: « le lieu que le Seigneur choisira (tm) ou a choisi (Sam) pour y placer son nom ». Elle est attestée deux fois en Dt 12 : 21 ; 14 : 24. En Dt 12 : 5, les deux formes se cumulent : « le lieu que le Seigneur choisira (tm) ou a choisi (Sam) pour y placer son nom et le faire habiter ». La troisième forme n’a pas de complément d’infinitif et se borne à constater le choix que le Seigneur fait du lieu : « le lieu que le Seigneur choisira (tm) ou a choisi » (Sam). Le Deutéronome s’en sert douze fois en 12 : 14,18,26 ; 14 : 25 ; 15 : 20 ; 16 : 7,15,16 ; 17 : 8,10 ; 18 : 6 ; 31 : 11. D’autres éléments comme l’épithète « ton Dieu » ou «parmi toutes les tribus» peuvent entrer dans la formule. Il n’est pas nécessaire de s’y arrêter ici.

Monday, April 16, 2012

How Does One Date an Expression of Mental History? The Old Testament and Hellenism

Niels Peter Lemche,

Professor of Department of Biblical Exegesis

Faculty of Theology

University of Copenhagen

In the good days of old—not so far removed from us in time—a biblical text was usually dated according to its historical referent. A text that seemed to include historical information might well belong to the age when this historical referent seemed likely to have existed. At least this was the general attitude. The historical referent was the decisive factor. If the information included in the historical referent was considered likely or even precise, the text that provided this information was considered more or less contemporary with the event—that is, the historical referent—although the only source of this event was often the text in question that referred to it.

In those days, everybody knew and talked about the 'hermeneutic circle'. It was generally accepted that the study of ancient Israel

Monday, January 16, 2012

The Story of Sheshbazzar

The book of Ezra tells us how after 70 years of Babylonian captivity the Jewish people returned to Judah and rebuilt Jerusalem Jerusalem

In the first chapter of the book (so called Story of Sheshbazzar) the Persian king Cyrus the Great issued an order and allowed the Jews return to Judah and rebuild the temple of Yahweh in Jerusalem. Then Cyrus sent to Jewish ruler Sheshbazzar the temple vessels which Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon brought from the temple of Solomon Babylon

Tuesday, November 1, 2011

Lester L. Grabbe, Ezra-Nehemiah (pdf)

The books of Ezra and Nehemiah have not been the most popular of the books in the Hebrew Bible. Yet they have had great influence on how the Jewish religion is assumed to have developed. They describe the reconstruction of the Jewish temple and state after their destruction by the Babylonians in 587/586 BCE and set the theme for the concerns and even the basis of Early Judaism which is usually seen as the Torah. The figure of Ezra has been profoundly associated with the origin or promulgation or interpretation of that Torah. The consequence is that the books of Ezra and Nehemiah are in many ways the foundation of much scholarship, not only about the development of the Jewish religion but even of how the Old Testament (OT) literature emerged.

The aim of this book is to make a contribution to a better understanding of these two books which, in my opinion, are crucial writings in the Hebrew Bible. My study has implications for the history of Israel and Judah Judah

Tuesday, October 4, 2011

The Two Recensions of the Book of Ezra: Ezra-Nehemiah (MT) and 1 Esdras (LXX)

Dieter Bohler

Abstract: Like Proverbs, Jeremiah and Daniel, the book of Ezra has been transmitted in two recensions: Ezra-Nehemiah in the Hebrew Bible and 1 Esdras in the Greek Bible. Each version has its own distinct literary shape. Both editions overlap in the account of Zerubbabel's temple building and Ezra's mission. In addition to this common material both versions contain special property: 1 Esdras starts with the last two chapters of Chronicles (Ezra MT

Saturday, July 23, 2011

Genesis and the Moses Story

Genesis and the Moses story were two competing myths of origin for Israel that were literarily and conceptually independent from each other. They both explained in different ways how Israel came to be.See also Genesis and the Moses Story: Israel’s Dual Origins in the Hebrew Bible (Siphrut 3; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2010)

By Konrad Schmid

Professor of Hebrew Bible and Ancient Judaism

University of Zurich, Switzerland

October 2010

In the 20th century, the so-called Documentary Hypothesis with its four elements J, E, P, D was a commonly accepted explanation for the literary growth of the Pentateuch. This hypothesis is based on the assumption that there are three similar narrative accounts of Israel's history of the creation, the ancestors, the exodus, and the conquest of the land: J, E, and P. The story line of the Pentateuch was considered very ancient. J adapted the structure of the narrative from the old creeds of ancient Israel, and the structure of the narrative accounts of E and P were mere epigones or imitations of J. However, in the last thirty years, serious doubts have arisen concerning this model. Only P, because of its clear structure and its specific language, has remained generally uncontested.

By Konrad Schmid

Professor of Hebrew Bible and Ancient Judaism

University of Zurich, Switzerland

October 2010

In the 20th century, the so-called Documentary Hypothesis with its four elements J, E, P, D was a commonly accepted explanation for the literary growth of the Pentateuch. This hypothesis is based on the assumption that there are three similar narrative accounts of Israel's history of the creation, the ancestors, the exodus, and the conquest of the land: J, E, and P. The story line of the Pentateuch was considered very ancient. J adapted the structure of the narrative from the old creeds of ancient Israel, and the structure of the narrative accounts of E and P were mere epigones or imitations of J. However, in the last thirty years, serious doubts have arisen concerning this model. Only P, because of its clear structure and its specific language, has remained generally uncontested.

Thursday, July 21, 2011

The Origin of Biblical Israel

Philip R Davies

I

The most important development in recent years in the study of the history of ancient Israel and Judah has been, in my opinion, the interest in Judah during the Neo-Babylonian period, a period previously somewhat neglected, and strangely so, since it offers the most peculiar anomaly: for the entire period, a province called ‘Judah’ was in fact governed from a territory that, as the Bible and biblical historians themselves would describe it, was 'Benjamin’. The former capital of the kingdom of Judah , Jerusalem

How long this state of affairs continued remains unclear: the narratives of Ezra and Nehemiah are silent about this (as they are confused about the rebuilding of the Temple), and, as Edelman has recently argued (Edelman 2005), Jerusalem was probably not restored as the capital of Judah until the middle of the 5th century at the earliest (indeed, if Jerusalem had been the capital before the time of Artaxerxes, the story of Nehemiah would be largely pointless!).

Thus, for well over a century, the political life of Judah was centered in a territory which had once been part of the kingdom of Israel Judah Judah Egypt or by Babylon Assyria .

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

LIBRARY

ATLASES

BOOKS

Biblical History:- Josephus "The Antiquities of the Jews"

- Walter Dietrich "The Early Monarchy in Israel. The Tenth Century B.C.E."

- Mario Liverani "Israel's History and History of Israel"

- Ahab Agonistes "The Rise and Fall of the Omri Dynasty"

- Lester L.Grabbe "A History of The Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period"

- Lester L.Grabbe "An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism. History and Religion of the Jews in the time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel and Jesus"

- Mario Liverany "Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography"

- Niels Peter Lemche "The Israelites in History and Tradition"

- Thomas L. Thompson "Jerusalem in Ancient History and Tradition"

Biblical Archaeology:

- Richard Plant "A Numismatic Journey Through the Bible"

- Israel Finkelstein & Neil Asher Silberman "The Bible Unearthed. Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts"

- Israel Finkelstein, Neil Silberman "La Biblia Desenterrada"

- Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, "David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition"

- Eric H.Cline "Biblical Archaeology. A Very Short Introduction"

- John C.H.Laughlin "Fifty Major Cities of the Bible"

- Yitzhak Magen & Yuval Peleg "The Qumran Excavations 1993-2004. Preliminary Report"

- Beth Alpert Nakhai "Archaeology and the Religions of Canaan and Israel"

- Archaeological Study Bible

- Neil Asher Silberman & David Small "The Archaeology of Israel. Constructing the Past, Interpreting the Present"

- Ian Shaw and Robert Jameson "A dictionary of archaeology"

- William G. Dever "Did God Have a Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel"

- Anne Katrine de Hemmer Gudme "Before the God in this Place for Good Remembrance. A Comparative Analysis of the Aramaic Votive Inscriptions from Mount Gerizim

History of Religions and Cults:

- Britannica Encyclopedia of World Religions

- Sarah Iles Johnston "Ancient Religions"

- Frank Moore Cross "Canaanite Myth And Hebrew Epic. Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel"

- J.C.L.Gibson "Canaanite Myths and Legends"

- Eva Pocs and Gabor Klasiczay "Christian Demonology and Popular Mythology"

- Raphael Patai "The Hebrew Goddes"

- Bob Becking & Marjo C.A.Korpel "The Crisis of Israelite Religion. Transformation of Religious Tradition in Exilic & Post-Exilic Times"

- Ahmed Osman "Christianity. An Ancient Egyptian Religion"

- Karin Finsterbusch, Armin Lange and K.F.Diethard Romheld "Human Sacrifice in Jewish and Christian Tradition"

- Tilde Binger "Asherah. Goddesses in Ugarit, Israel and the Old Testament"

- Etienne Nodet "A Search for the Origins of Judaism"

- J.Glen Taylor "Yahweh and the Sun. Biblical and Archaeological Evidence for Sun Worship in Ancient Israel"

- Elizabeth Bloch-Smith "Judahite Burial Practices and Beliefs about the Dead"

- Magnar Kartveit "The Origin of the Samaritans"

Biblical Criticism:

- P R O L E G O M E N A to the HISTORY OF ISRAEL. by JULIUS WELLHAUSEN

- Giovanni Garbini "Myth and History in the Bible"

- Richard Elliott Friedman "Who Wrote the Bible?"

- Richard Elliott Friedman "The Bible with Sources Revealed"

- Ingrid Hjelm "The Samaritans and Early Judaism. A Literary Analysis"

- Emanuel Tov "Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible"

- Philip R.Davies "Whose Bible Is It Anyway?"

- Philip R.Davies and David J. A.Clines "Among the Prophets. Language, Image and Structure in the Prophetic Writings"

- Leon Vaganay "An Introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism"

- Michael Fishbane "Biblical Myth and Rabbinic Mythmaking"

- Barry G.Webb "The Book of the Judges. An Integrated Reading"

- Kenneth C.Davis "Don't Know Much About the Bible. Everything You Need to Know About the Good Book but Never Learned"

- William M.Schniedewind "How the Bible Became a Book"

- Steven L.McKenzie and M.Patrick Graham "The History of Israel's Traditions. The Heritage of Martin Noth"

- Rolf Rendtorff "The Problem of the Process of Transmission in the Pentateuch"

- David T.Lamb "Righteous Jehu and His Evil Heirs. The Deuteronomist's Negative Perspective on Dynastic Succession"

- Rutherford H.Platt, Jr. "The Order of All the Books of the Forgotten Books of Eden"

- Karen Armstrong "A History of God"

- Martin Noth "The Chronicler's History"

- R.N.Whybray "The Making of the Pentateuch. A Methodological Study"

- Richard D.Nelson "The Double Redaction of the Deuteronomistic History"

- The Earliest Text of the Hebrew Bible. The relationship Between the Masoretic Text and the Hebrew Base of the Septuagint Reconsidered. Ed. by Adrian Schenker

- John Van Seters "Pentateuch: A Social Science Commentary"

- Lester L.Grabbe "Ezra-Nehemiah"

- Lester L.Grabbe "Did Moses Speak Attic? Jewish Historiography and Scripture in the Hellenistic Period"

- Ingrid Hjelm "Jerusalem's Rise to Sovereignty. Zion and Gerizim in Competition"

- Thomas L. Thompson "The Origin Tradition of Ancient Israel. The Literary Formation of Genesis and Exodus 1-23"

- David J.A. Clines "The Theme of the Pentateuch"

Dead Sea Scrolls:

- James H.Charlesworth "The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Princeton Symposium on the Dead Sea Scrolls"

- The Dead Sea Scrolls. The Ancient Library of Qumran and Modern Schoolarship

- Jonathan G.Campbell "Deciphering the Dead Sea Scrolls"

- Donald W.Parry & Emanuel Tov "Dead Sea Scrolls Reader. Texts Concerned with Religious Law"

- Donald W.Parry & Emanuel Tov "Dead Sea Scrolls Reader. Exegetical Texts"

- Donald W.Parry & Emanuel Tov "Dead Sea Scrolls Reader. Calendrical and Sapiential Texts"

- Frederick H.Cryer & Thomas L.Thompson "Qumran Between the Old and New Testaments"

- Hershel Shanks "Understanding the Dead Sea Scrolls"

- C.D. Elledge "The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls"

- David L.Washburn "A Catalog of Biblical Passages in the Dead Sea Scrolls"

- Hanan Eshel "The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonean State"

- Emanuel Tov "Hebrew Bible, Greek Bible, and Qumran Collected Essays"

- Dorothy M.Peters "Noah Traditions in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Conversations and Controversies of Antiquity"

- Florentino García Martínez & Eibert J.C. Tigchelaar "The Dead Sea Scrolls. Study Edition"

- Peter W.Flint "The Bible at Qumran. Text, Shape, and Interpretation"

- Philip R.Davies "The Damascus Covenant. An Interpretation of the Damascus Document"

- Florentino García Martínez "The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated. The Qumran Texts in English"

is where my documents live!

is where my documents live!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)